Fritz Haber

Benjamín Labatut's book When We Cease to Understand the World1 mentions the German chemist Fritz Haber a few times.

Not being up on my history of twentieth century sciences, Haber's story was stunning. His Wikipedia page doesn't do him justice.

Depending on your point of view, he's either the greatest saviour of humanity or the cause of its ultimate future demise.

Did you know that before Haber came along it was very common for wars to be fought over decomposed bodies? That the remains, full of nitrates, were bought back to the victor's homeland to fertilise crops? That cemeteries, mass graves, the Egyptian tombs sealed with the remains of thousands of slaves, were ransacked for the nitrogen in those dusty decayed bones by empires large and small?

Haber singlehandedly ended that practice. He won the Nobel prize for inventing a process which pulls nitrogen out of the air in the form of ammonia. It's a technique which happens at a massively industrial scale and is key to modern agriculture. Without that synthetic ammonia, there would be nowhere near enough nitrates available to fertilise everything humanity needs to eat.

In a sense, Haber is responsible for the cheap, easy to access food across the entire globe. Everything from a rice field in Asia to a cattle ranch in Argentina and anything in between could not produce a tenth of the produce it does without artificial fertiliser. And without that sustenance, our population would be unable to survive.

All positives have a negative, including this.

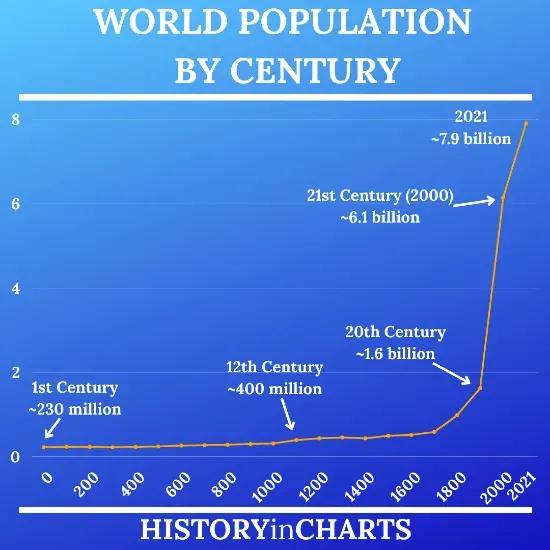

Cheap and easy access to food means that the horror of starvation, of Dust Bowl-like famine, of general lack of nutrition is gone. The food available to mankind acted as a limiter on population growth: a certain amount of possible calories means only a certain amount of people can survive. A massive increase in fertiliser means a massive increase in produce which, undoubtedly, was one of the major causes of the massive increase in population seen over the course of the twentieth century:

(Chart sourced from History In Charts)

The increase in population has all sorts of consequences: overconsumption of other natural resources, climate change, etc.

But if humanity suddenly vanished tomorrow, Haber would still have an awful impact on the world. There's billions upon billions of tonnes of artificially sourced fertiliser now in existence, far more than the planet had or needed. As Labatut notes, if we disappeared it's likely that plantlife would not only flourish but pretty much overwhelm the soil and the biosphere as a whole.

How to consider the progress enabled by Haber? A boon to humanity, allowing more people to be born and to survive, or a global terror responsible for many of the problems we now experience?

I think it's possible - and reasonable - to both-sides this one. More food has decreased overall suffering, a prevalent problem in the early 1900s. The problems of the early 2000s - including those that came as a result of this innovations - are for us to solve.

Oh, and he also enthusiastically developed chlorine gas for military use in World War One despite it breaking an international agreement and watched its first use at Ypres with relish.

A truly excellent book that I cannot recommend enough. On my /now page at the time of reading I described it as "Dizzyingly enthralling. It's a short book and I'm not very far in yet, but it's like a seven-year-old's stream of consciousness around related topics but with the knowledge and perspective of someone who knows the world, knows history, knows chemistry and science. The first chapter, "Prussian Blue", is the most astonishing thing I've read in years."↩